An Abridged History of The Skeleton 2 and Post-Transhumanism by R.C. Joseph [Issue #12 Full Story]

AS SEEN IN PLANET SCUMM #12

Written by R.C. Joseph

Illustrations by Sam Rheaume and Kels Hyde

An Abridged History of The Skeleton 2 and Post-Transhumanism

R.C. Joseph

FleshTech shares exploded ahead of their magnum opus, whose fraught history is often called “the near demise of the cybernetics market.” Though panned in pop culture as "the most disappointing product of all time," and "the un-invention of the wheel," FleshTech's famous failure revolutionized human augmentation.

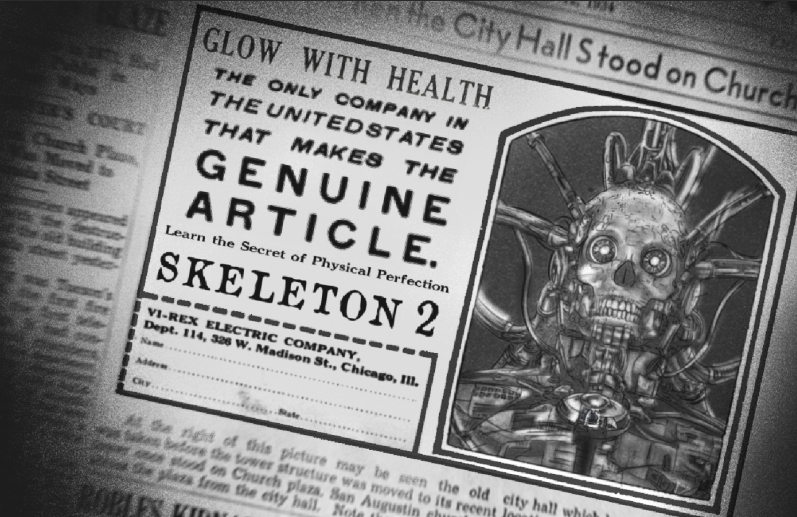

Released to general acclaim in the year 2136, the project, colloquially known as "The Skeleton 2," was touted as "an answer to original human bones." (The device's actual, patented name has been lost to history. "Skeleton 2" was coined by social media immediately after its announcement.)

When exploring the features of the ill-fated implant, the mockery it faced has blurred fact and fiction. Inclusions most agreed upon by scholars include: a color-changing light-up ribcage, extendable legs for "being tall on the go," a 360-degree neck, and app support. Others, such as "patting your head while rubbing your tummy to take a screenshot," have since been debunked.

The main allure of "The Skeleton 2" came from its most bold and controversial feature—a complete lack of joints. FleshTech CEO Sophia Massey, in an interview with Martian 60 Minutes, identified joints as the greatest shortcoming of the body's organic scaffold, citing how they're often the first to decline. Instead, her framework was a semisolid alloy, which could be selectively shaped with neural input from the user. (FleshTech represented the first commercial use of this alloy, which had been developed several years earlier in the Asteroid Belt settlements. The history of the material, and its role in the cybernetics boom of the 2130s, is outlined in Digging for Bones by Dr. Louis Melendez.)

The first known usage of "The Skeleton 2" moniker occurred in July of 2135, on the social media platform Groupie. A blurry photograph of the FleshTech website, as displayed on a holoscreen, was uploaded by user Hunk0fMet4l, with the following caption:

"y'all they made a skeleton 2"

This post received 600,000 likes in under eight hours, and over 5,500 comments, most of which were "SKELETON 2!". Its prompt successor was another photo from the same user, depicting a cybernetic hand holding a tabby, captioned "WE GETTIN' SOME BONES, BOYS!". This post crested a million likes in the following week, and is considered to be the first official “Skeleton 2” meme. Its unexpected popularity is viewed by economic historians as a key factor in the product’s earth-shattering fall from grace.

In subsequent months, billions of posts were made about the device. Digital anthropologists have recovered numerous photo manipulations, in which a human skeleton with the number "2" on its forehead was crudely edited into various scenes. (This depiction persisted even after the real design was unveiled in November of 2136.) Chosen placements for "The Skeleton 2" have no obvious connection to one another, ranging from family photos to Sandro Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus." FleshTech shared many of these on their official account, seldom credited. When criticized for this behavior, they announced a "meme contest," and declared posts on their feed to be entries. The diversion succeeded, but battle lines were drawn between FleshTech supporters and detractors. Sophia Massey's personal account acquired followers at a dizzying pace, as self-proclaimed tech buffs declared her "the future of human augmentation."

Despite her fame, Massey's company employed only 50 people in the summer of 2136. Typical mass market vendors in the 22nd century employed thousands or more. BotBod, the leading cybernetics provider of the era, employed more than 10,000 individuals across Earth and Io. Only boutiques crafting made-to-order pieces, for a wealthy few, were of similar size to FleshTech. At the time of Massey's interview, it barely outsized Exquisite Corpse, one of the most exclusive luxury houses. Yet she was almost a more frequent feature than her wares. (Her life, and eventual cult of personality, are explored in the 2139 documentary No Bones About It, including her scrapped weaponized "Skeleton 2.")

The earliest hints of woe came in June of 2136, when FleshTech promised, and failed, to demo their product for augmentation enthusiasts at CyborgCon. Billed as the main event, the presenters struggled to satiate fans for two days before a less-than-functional concept appeared at the end of the convention.

This coincided with a scathing thread on Groupie. An anonymous user began feverishly posting in the latter half of CyborgCon, warning of crunch conditions at FleshTech headquarters. Prototype "Skeleton 2s," they insisted, were not nearly what Massey had promised consumers. Rather than admit hubris, she had extended hours significantly, and for little to no bonus pay. FleshTech fiercely denied these claims, blaming their convention blunder on a unit "damaged in transit." Massey hosted a private presentation at the company's headquarters several weeks later. Her personal Groupie account discussed only this event, ignoring comments on CyborgCon completely, except to "like" those defending her. Few images exist of the "Skelebration," though one attendee was reportedly injured after drunkenly tripping over a custodial droid. This would be the first of many rambunctious functions curated for Massey's growing entourage.

The bad publicity did little damage to sales, however. Many orders are believed to have been jokes, as the trend continued even when it was apparent that FleshTech couldn't meet demand, despite renting out BotBod's plant on Io. Massey encouraged bulk purchases on social media, both as gifts and for personal use. She even offered to buy fans' current skeletons so they could "make room,'' though this is not believed to have actually happened, as it was, and is, illegal.

Recovered Groupie posts suggest absurd "Skeleton 2" orders may have even been a meme, as FleshTech critics mocked fan fervor. A popular Groupie post from November 2136 proclaimed, "You're buying a Skeleton 2? Pathetic. I'm buying ten." Pop culture journalists scrambled to ride the wave, and the resulting news avalanche remains a trove for historians.

Dismissing delay rumors, FleshTech unveiled "The Skeleton 2" on December 12, 2136. In the subsequent month, several issues arose.

The extendable leg feature was disabled in a software update three weeks after release. This followed multiple consumer complaints that their muscle tissues were incompatible with the feature, and began to hold excessive length after repeated use.

The biolink software responsible for connecting the apparatus to the user was found to have security vulnerabilities. Internet trolls pounced, unleashing a virus which caused infected units to dance uncontrollably. To combat this, a firmware update ceased device operation if the server connection was lost—its broad application resulted in some users becoming suddenly immobilized during internet outages, or while traveling in rural areas.

FleshTech's biolink software was also proprietary, and incompatible with competitor products. Consumers with multiple brands of augmentations were forced to purchase expensive adapters. Massey initially defended this decision, claiming "The Skeleton 2" was a complex and ambitious machine, and should not be managed by third parties for safety reasons. The matter became an interplanetary headline following a lawsuit by customer Kendra Sherman, who alleged that competing biolink softwares active in her body caused her "Skeleton 2" to become trapped in a feedback loop, repeating motions needlessly for increasing long periods. This led to her being forced to take an hours-long “leisurely stroll” through her home city of New Glasgow until she managed to cry out for help from passersby.

Despite negative press, the public seemed to fall in love with FleshTech's problem child. Sites such as Groupie were flooded with memes and videos of the malfunctioning "Skeleton 2." Rumors spread that FleshTech petitioned for the removal of unflattering posts, tripling the speed at which they were shared.

Popular videos depicted groups participating in the “Boneless Challenge,” where “Skeleton 2” users would wander rural fields at night with only their brightly flashing ribcages visible, until one or more participants lost network connection and collapsed motionless to the ground. A brief moral panic ensued.

By New Year's Day, 2137, FleshTech had logged over 8.6 million customer service tickets. To meet this demand, the company took on 2,000 independent contractors, and opened multiple massive call centers. (Between January 3rd and February 14th of 2137, a FleshTech call center employed every resident of Bedford, Iowa. The story of this center is detailed in Skeletons in Our Closets, by Binh Nguyen.)

While unpopular with shareholders, the move served to plateau declining sales. By January 15th, service costs no longer impeded profits. This pattern held until February 6th, when "The Skeleton 2" encountered its final performance failure.

The alloy which comprised the artificial bones had not been tested for all climates. Many users in tropical locales reported units becoming excessively semisolid on humid days. This resulted in them destabilizing, particularly in the areas where joints would have been. Images of this phenomenon were largely removed from Groupie as community guidelines violations. Surviving posts describe it as "like cartoon arms, but in real life."

FleshTech shares continued to plunge through February of 2137, as the company declared it was unable to process returns or refunds. Massey gave a tearful press conference from her backyard pool, bemoaning "the challenges and limitations of running a small business," and thanking "everyone who bet on the future of bones." Fans who had purchased multiple units at Massey's behest lamented their investment publicly, with many losing a great deal of money. Groupie saw frequent clashes between bitter buyers and Massey loyalists, amplified by the "Skelegy" farewell concert held at her home several weeks later.

In an attempt to save face, FleshTech announced the upgraded model 2XM for the fall of 2137, featuring improved dexterity, self-cooling, and an optional rose-gold finish. There is currently no evidence that this model was ever released.

Surviving documents suggest unsold units were launched into space. The specifics of this disposal were lost, along with most financial records, when FleshTech abruptly closed at the end of 2137. Historians have refocused their search to employees' personal logs.

Like the story?

Put it on your bookshelf!

Successfully uninstalled units were a highly sought collectible until 2139, when the alloy which comprised the artificial bones proved medically useful for joint replacement, which saw the skeletons disassembled and melted. No intact, functional "Skeleton 2s" have yet been located for further study.

As the 2130s closed, the failure of "The Skeleton 2" was the final blow to the cybernetics boom. Public attitudes continued to sour, leading to a 20-year decline in recreational biomechanics, known today as the Post-Transhumanist movement.

Post-Transhumanism, weary of machine evolution, sought to do things the new-old-fashioned-way. Organic life was not so much favored as flaunted.

Beginning with the "Accordionpunks" and their flexible namesake limbs, the new age flirted with an analog ascension. Then came the designs of Deirdre Ryan. A part-time apiculturist, she employed a system of pheromones, and replaced her prosthetic arm with a swarm of friendly bees.

Though perhaps most curious of all were the Abstract-Post-Transhumanists, who scoffed at any artificial sublimity. Gone were the days of humans made machine. Instead, they championed the machine made human, by “uploading” a computer's mind into an organic body. (The tumultuous tale of “Transmechanism,” as it came to be known, is explored in Dr. Rebecca Leger’s The Semi-Artificial Life of the Miraculous Meat Computer, a three-volume series on the cow that appeared at the 2155 World’s Fair, allegedly a neural network in a cow’s body.)

While its unorthodox approach has found a place in modern extrasolar living, Post-Transhumanism tragically retained the weakness of its ancestor.

In a lust for gossip, Groupie ignited another viral scandal. This one alleged that an Iopian teen, egged on by memes, paid startup NewU to replace his skeleton with an exoskeleton. In the spirit of the times, he received a roll cage made of lab-grown bones. Disconnected from a body, it unfortunately required a bulky computerized life support, and regular infusions of blood.

Suddenly a laughingstock, NewU closed in the summer of 2163. Bankruptcy proceedings followed a dubious stream of venture capital back to one Sophia Massey. She was arrested at her Martian home and charged with embezzlement and reckless augmentation of a minor. Fascination with the movement dwindled shortly after. The top comment on Groupie read simply:

"we did it, the skeleton 3"

A Pennsylvania cryptid, R.C. Joseph writes, draws, and still uses her original skeleton. Speculative fiction is her jam. When she isn't growing her plant collection, she can be found cooking with friends, or on Twitter @perihelianthus.